Note: This is a guest blog by Helmut Jäger. Dr Jäger’s website and blog provides more information and thoughtful comments on healthcare issues at: http://www.medizinisches-coaching.net/

Good news: hepatitis C can be cured

Since 2016, the World Health Organization recommends treating hepatitis C infection with sofosbuvir (NS5B-Polymerase-inhibitor). The manufacturer (Gilead) demands an extremely high price, and

“.. the public paid twice: for the pharmaceutical research and for the purchase of the product. The enormous profits flow to the Gilead shareholders.”(Roy BMJ 2016, 354: i3718)

The evidence for the effectiveness of direct-acting antivirals (DAA) for chronic hepatitis C comes from short-term trials. Cochrane is unable to determine the effect of long-term treatment with these drugs:

DAAs may reduce the number of people with detectable virus in their blood, but we do not have sufficient evidence from randomised trials that enables us to understand how SVR (sustained virological response: eradication of hepatitis C virus from the blood) affects long-term clinical outcomes. SVR is still an outcome that needs proper validation in randomised clinical trials. (Cochrane 18.09.2017: http://www.cochrane.org/CD012143/LIVER_direct-acting-antivirals-chronic-hepatitis-c.)

Egypt is particularly affected by hepatitis C. Here the government negotiated special discounts with Gilead, so that relatively cheap treatment will be available. It’s the foundation of just another lucrative business based on a man-made disaster.

Tour’n Cure: The profitable medical eradication of a problem that would not exist without medicine.

Bad news: Hepatitis C will still be transmitted by skin piercing procedures

About 2-3% of the world’s population is infected with the hepatitis C virus (HCV); 350,000 of these 130-170 million people die per year. HCV causes liver infections, which are chronic in more than 70% of infected persons. That is, they do not completely cure after an infection. After one or maybe two decades, the damaged liver can fail, or develop cancer. The survival rates are low in the late stages of the disease, even under optimal treatment conditions.

Hepatitis C viruses are very sensitive to environmental influences so they are transmitted almost exclusively through blood or blood products or unclean syringes. Unlike hepatitis B or HIV/AIDS, HCV infections through sexual contacts are rare. Hence, the incidence of HCV is an indicator of a dangerous handling of needles, syringes, other medical instruments or products that lead to a direct blood contact. And new cases of HCV are acquired most likely in health care facilities or by intravenous drug use.

Treatment of disease and prevention of new infections

The World Health Organization (WHO) announced in 2016 that it wants to “combat” hepatitis C and “exterminate” it by 2030. (WHO 2017: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs164/en/)

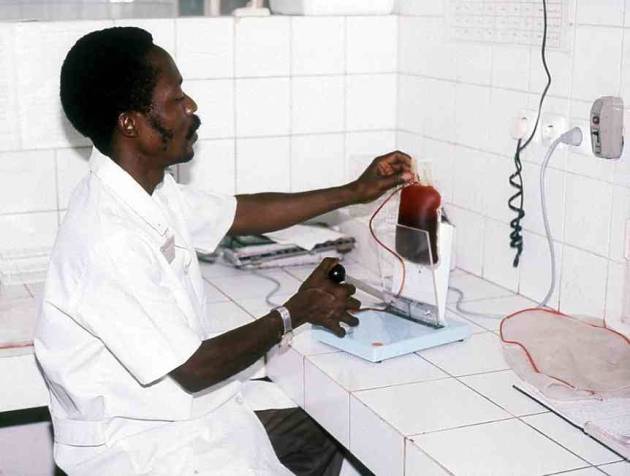

Hazardous needles somewhere in Africa (image: Jäger, Kinsahsa 1988)

WHO’s optimism is caused by the availability of sofosbuvir. The drug is said to have cured up to 90% of affected patients in clinical trials, and consequently was added to the WHO list of essential medicines. The pharmaceutical company Gilead faces a huge global market with high profit margins (WIPO 2015): The treatment costs in the US are US$84,000 and in the Netherlands €46,000. The production cost of the drug is estimated not to exceed US$140.(‘T Hoen 2016)

Most people affected by hepatitis C are poor. They now learn through the media that their suffering could be cured, and at the same time that this solution seems to be unavailable to them. Consequently, they will demand the necessary funds for humanitarian reasons from their governments. Gilead expects sofosbuvir will not be manufactured and sold without a license (about 100 times cheaper). The Indian authorities already concluded in 2016 a license agreement with Gilead, which will guarantee high profit rates on the subcontinent.(‘T Hoen 2016)

Attractive medical products and markets increase the risk of the production of counterfeit medicines

In India, the requirement to allow the production of the hepatitis C drug in the “national interest” license-free is not only risky for legal reasons. India already is the world’s leading producer of fake medicines. Counterfeit drugs look exactly like real ones, but contain nothing (in the best case) or poison. About 35% of the malaria drugs in the African market are fake or useless, and they are mostly from India or China (see below: fake drugs). In the case of Egypt, medical institutions tried to open up a lucrative international market (“Tour’n cure”). Therefore, it will not be long until the first fake “sofosbuvir preparations” are offered.

The history of the hepatitis C epidemic in Egypt

The disaster of hepatitis C contamination started in Egypt more than sixty years ago. Efforts to regulate the Nile increased the risk of schistosomiasis infections. These parasites cause numerous health problems, mostly in the pelvic organs, and in rare cases, cancer. The worm larvae swim in stagnant water that has been contaminated by human urine or feces, and they enter the blood system of healthy people by piercing the skin.

The frequency of these worm infections increased rapidly after 1964, when the fast-flowing Nile was tamed by the Aswan Dam. In a relatively short time 10% of the Egyptian population was colonized by the parasite. The Ministry of Health then treated large parts of the population with injections containing antimony potassium tartrate. Until 1980 this toxic compound was considered the only effective remedy for this worm-infection. Today it is no longer used, not even in veterinary medicine.

Many years after the start of the campaign an initially unexplained epidemic of hepatitis C was noticed in Egypt. It turned out that most of the patients with hepatitis C virus received anti-schistosomiasis injections.

Those initially infected with hepatitis C virus had higher risks to be treated in health care facilities, where the virus was then transmitted to other patients. Today (according to different estimates) 3-10% of the Egyptian population is infected with hepatitis C, and 40,000 patients die per year with the disease. Because many patients are infected, today the risk to acquire hepatitis C infection in Egyptian health facilities, even in optimal hygenic conditions, is significantly higher than in countries where hepatitis C is relatively rare.(Strickland 2006, WHO 2014)

Hepatitis C epidemic in industrialized countries

But Egypt is not an isolated case. Hepatitis C affects mostly the residents of developing and emerging countries. But even in Germany more than half a million HCV infections are recorded.

In England, in 2015 the government had to apologize for the infection of nearly 3,000 people who received infected blood products between 1970 and 1990.(Wise 2015)

In the US hepatitis C is called a “hidden epidemic” because 300,000 people were infected each year a few decades ago.(Ward 2013, Warner 2015, CDC 2015, RKI 2015, Pozzetto 2014)

Syringes and blood products are dangerous if handled improperly or if they are used although they are not necessary

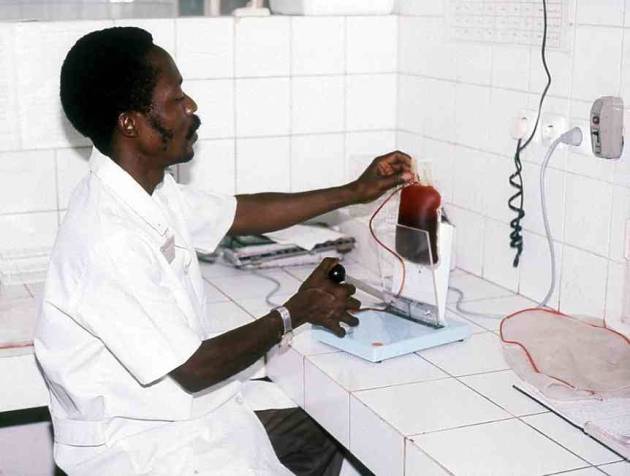

Blood Bank in Kinshasa (Congo, 1990, image: Jäger)

Needles (in particular the worldwide introduction of disposable syringes and their inflationary use) contributed to the spread of viruses like HCV, HIV and others.(Jäger 1990-92) The problem of the HCV epidemic is caused by the health care system and its waste products that fall into the wrong hands. The causes of the infections mostly are: bad medicine or intravenous drug addiction. What happened in Egypt is just another example that sometimes (medical) solutions of seemingly controllable health problems can lead to much larger problems: because sometimes “the things bite back.”(Tenner 1997, Dörner 2003)

Therefore WHO’s strategy to eradicate hepatitis C, based only on treatments, cannot succeed as long as the much of the medical sectors in many poor countries remain dangerous-purely-commercial and in large parts uncontrolled. The WHO campaign certainly will enrich Gilead and some health institutions, but a reduction of the hepatitis C incidence will not take place if “bad medicine” and “drug addiction” are not targeted, preferably eradicated, or at least reduced.

Unnecessary medicine is risky and should be avoided

WHO and other international health organizations should strive to avoid unnecessary therapeutic skin piercing procedures, injections, surgery and transfusions, and (if these sometimes life saving procedures are necessary) establish strict quality control. The commerce of medical tourism and beauty-interventions (botox, piercing, tattoo) should be strictly controlled.

Hazardous needles anywhere else in Africa (image: Jäger)

And we should invest in training patients: They should be supported to reduce their demand for health-care-products and to increase their knowledge in order to distinguish “good” and “bad” medicine.

More

Literature

- CDC: Health Care-Associated Hepatitis B and C outbreaks, reported to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) 2008-2014

- Pozzetto P: Health care assoziated hepatitis C virus infection, World J Gastroenterol 2914 2014 Dec 14; 20 (46): 17265-78.

- RKI: Epidemiological Bulletin No. 38, 2011and guide for doctors in 2015

- Roy V et al .: Betting on hepatitis C: how financial speculation in drug development influences access to medicines. BMJ 27/07/2016 354: i3718

- Strickland GT: Liver Disease in Egypt: Hepatitis C Superseded schistosomiasis as a result of Iatrogenic and Biological Factors, Hepatology, 2006, 43 (5) 915-922

- ‘t Hoen E: Indian hepatitis C drug patent decision shakes public health community.Published online May 26, 2016 – mail correspondence: medizinisches-coaching.net/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/Hepatitis-C-Elimination-2016.docx?x47477

- Ward JW: The hidden epidemic of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States: occult transmission and burden of disease. Top Antivir Med 2013 Feb-Mar; 21 (1): 15-9.

- Warner AE: Outbreak of hepatitis C virus infection associated with narcotics diversion by in hepatitis C virus-infected surgical technician Am J Infect Control. 2015 Jan; 43 (1): 53-8. doi: 10.1016 / j.ajic.2014.09.012. Epub 2014 Nov. 20.

- WHO 2016: Hepatitis C elimination by 2030

- WHO: Egypt steps up efforts angainst hepatitis C (July 2014) and Fact Sheet Hepatitis C in 2014

- WIPO: 2015 (Gilead): Global Hepatitis C Eradication

- Wise J: UK apologizes for contaminated blood scandal, BMJ, 04.04.2015, page 3

Bad Medicine in economically weak countries (such as “fake drugs”):

Why things bite back