Uganda is frequently mentioned in glowing terms in articles about HIV, especially in relation to the late 80s, 90s and early on in the 2000s. In contrast, Cuba is rarely mentioned in glowing terms, although the percentage of 15-49 year olds infected with HIV (prevalence), at 0.3%, is 23 times smaller than the same figure for Uganda, which stood at 7.1% in 2015 (all HIV figures from UNAIDS).

In fact, one could suggest that Uganda never got to grips with the epidemic. They still can’t explain why so many people, said to face a low risk of being infected with HIV, have seroconverted over the past several decades. Despite huge amounts of research, money and other resources being thrown at the country, the bulk of published research on HIV in Uganda seems to be focused on assumed sexual behavior and assumed sexually transmitted HIV.

Little or no international funding went into the HIV epidemic in Cuba. The country worked hard to research the epidemic, even before the first HIV positive person was identified there, several years before. Luckily, the country had a well developed health service, with more doctors per patient than any other high prevalence country (including the US). Indeed, the US (where an estimated 1.2 million were living with HIV in 2013) seemed intent on ridiculing Cuba’s approach to the virus.

Some of the criticisms were directed at claimed human rights aspects of Cuba’s achievements. It was often stated or implied that men who have sex with men were especially targeted by, for example, Cuba’s imposed ‘quarantine’. The quarantining started when little was known about the course of the illness, but it was relaxed once more was known. A number of personal accounts, some from men who have sex with men, now make it clear that many of the people quarantined are grateful to have received the care they got at the ‘sanitaria’ (there are links to other similar articles from this article).

An article by Tim Anderson finds that the quarantine did not target men who have sex with men; it also finds that other procedures were carried out in accordance with international guidelines. Anderson notes that Cuba was ‘more thorough’ in their testing and tracing procedures. Cuba has continued to make improvements in how they deal with the epidemic, which is a low level one, with men who have sex with men being the most affected group.

Sarah Z Hoffman refers to Cuba’s HIV program as ‘the most successful in the world’. Cuba approached HIV with the aim of reducing the likelihood of those infected going on to infect other people. That may sound like an obvious aim, but the greater thoroughness of Cuba identified by Anderson can be contrasted with a reduction in contact tracing in many countries, where it was claimed that certain groups were being unfairly targeted by such measures.

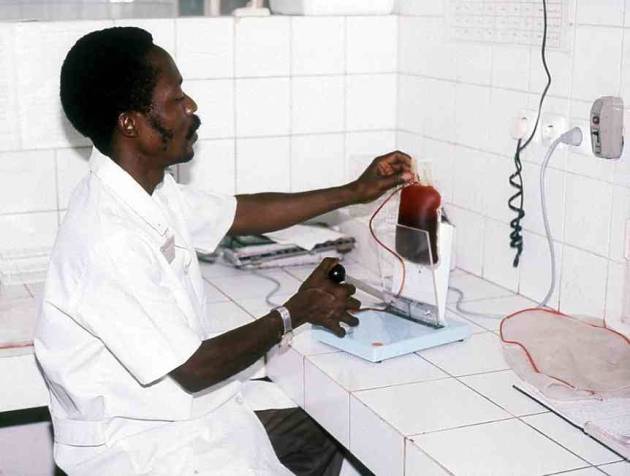

Cuba also started providing all HIV positive people with antiretrovirals in 2001, which they produced themselves as generic versions. Other countries had to wait a long time before they could provide more than a small fraction of HIV positive people with ARVs, and they had to pay astronomical amounts of money for them for years (although the costs are far lower now).

Hoffman writes “HIV infected people must provide the names of all sexual partners in the past six months, and those individuals must be tested for HIV. People found to have any sexually transmitted disease must undergo an HIV test as well. Voluntary HIV screening is encouraged.”

This is one of the places where practices in Cuba differ from practices in most other countries. This is called ‘contact tracing’ and it’s a vital tool of infection control. But in most countries people can claim anything they wish to about their sexual partners, that they have never had sex, that they have only engaged in heterosexual sex, that they have never injected drugs, etc. If people can withhold such information then contact tracing is impossible.

(My previous post is about a rare and valuable contribution to the history of HIV in Africa from John Potterat’s book ‘Seeking the Positives’, much of which concentrates on his work on HIV and STI epidemiology in the US. There’s a link to the chapter here. The approach the US adopted towards HIV could hardly have been more different from that of Cuba. Unfortunately, most other countries, certainly most poor countries, wedded themselves to the US, till death…etc.)

As a result of not tracing contacts, or of not doing so very assiduously, countries like the US, with extremely high transmission rates in certain groups, have never got their epidemic under control. In common with Cuba, the largest proportion of new HIV infections now is among men who have sex with men. Unlike Cuba, there is also a large injecting drug population in the US. But where contacts are not traced, they can not be offered the same opportunity to avoid infection if they are negative, or avoid infecting others if they are positive. Nor can they be ‘connected to care’ as quickly as possible.

In fact, many of the things western countries write copiously about, such as early testing and treatment, universal testing, elimination of mother to child transmission, universal access to treatment, were achieved in Cuba years ago, but have never been fully achieved even in some western countries. Where HIV prevalence is highest, in southern and eastern African countries, some of those achievements may not be realized in our lifetime.

Unfortunately for the worst affected countries, the rights of individuals are claimed to be foremost. Their contacts, past and future, are not treated as individuals. If the individual has multiple partners and chooses not to reveal that they engage in high risk practices, that’s considered to be the individual’s business. If the individual has had no sexual partners, or no HIV positive sexual partners, then the source of their infection needs to be identified. But in high prevalence African countries tracing of non-sexual contacts is rare. What you do find a lot of in research is findings referred to as ‘biased’, because the researcher expected every HIV transmission to be a case of sexual transmission.

(Despite the apparent desire of most countries to protect people’s individual rights in relation to HIV, this approach seemed to go out the window when the virus involved was ebola. Some ‘infection control’ measures seemed to involve groups breaking into people’s houses, forcing them into shabby health facilities, burning their property in public, spraying their houses, breaking up families and communities, etc. Who knows what approach will be taken to the next headline grabbing epidemic.)

So why all the attention and resources for a country that appears to have lost control of HIV a long time ago, and why all the rhetorical questions about Uganda, how their ‘success’ can be replicated, etc? More importantly, why so little attention for Cuba, and why is it so belated? We can learn a lot from both countries. Instead, we should be asking what Cuba did right, and continues to do right, but what Uganda did wrong, and continues to do wrong.

Cuba’s approach to HIV may have been the most successful anywhere. Some would go further and claim that Cuba may be the only country that was seriously threatened by the virus, but gained complete control over the epidemic early on, and retained that control. In the sphere of human rights, also, Cuba has made a lot of progress. Uganda, on the other hand, continues to move in the opposite direction in the fields of public health, human rights, HIV, political stability, economy, etc.