I mentioned some historical factors in Part II, so I’ve put together a timeline for Kenya’s epidemic, which seems appropriate in a history, especially a quick and dirty one. Some of the factors involved in HIV epidemic spread date back to the beginning of the century (or the beginning of humanity in the case of population). The table only lists some factors that have played, or are said to have played, a significant role; others will crop up later.

[Click on image to expand]

These factors would not have made it in any way inevitable that HIV would spread rapidly in certain places, more slowly in others and hardly at all in a few. That’s not what I’m arguing here. But there is an exception, a factor which doesn’t yet appear in the above table. Unsafe healthcare facilities to which the majority of a population has access render outbreaks of certain diseases more likely, and probably facilitate the exponential growth of some of those diseases more efficiently than any other factor possibly could. This is not true for HIV alone (or even MRSA in wealthy countries). TB can spread in health facilities (though deep mines are likely to be far more notorious in this instance), as seen in the case of Tugela Ferry in South Africa. Hepatitis C (and B) has often been spread widely through public health programs, such as in Egypt. Ebola is also very easily spread this way, and early accounts from some outbreaks are fairly explicit about this. Many of the people infected in the current outbreak are healthcare personnel. Many more were likely to have been infected by contact with other infected people in health facilities, perhaps even through contact with doctors and nurses (either because the doctors or nurses were infected or because their protective clothing was contaminated). Unsafe healthcare, as mentioned in Part II, is said to have ‘kickstarted’ the HIV epidemic. But conditions in healthcare facilities in African hospitals are appalling, so unsafe that the UN warns its employees not to use them. Tourists are warned to avoid injections and other procedures, even to carry their own injecting equipment. It’s only Africans themselves who are urged to go to health facilities and public health programs, without any warnings about unsafe practices or risks.

What is inevitable is that, if there is ever an outbreak of a disease that can be spread through unsafe healthcare, it will result in a serious epidemic in countries where conditions in healthcare facilities are unsafe. Such outbreaks have been documented in the case of HIV in Libya, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Romania and other countries. But the possibility of such outbreaks in sub-Saharan African health facilities has not been investigated. Or, if such an occurrence has been investigated, the findings have never been published.

So there were political, economic, environmental, ecological, demographic and various other factors in play long before HIV first reached Kenya, said to be some time in the 1950s. They are briefly mentioned in the above table because they need to be explained, which requires some historical detail (more than a superficial account is beyond the scope of this post). Therefore, I shall jump to the end of the colonial period right now and address remaining issues another time.

The first 10 or 15 years of independence saw a lot of progress in Kenya, especially in education and healthcare. Spending increased to provide these and other services for everyone, rather than the select few who would have had access to them before independence. The relative prosperity of this period was short lived. Global and more local economic and political events in the 1970s and 1980s would have already begun to interrupt progress. But the need to accept loans from the World Bank and the IMF, which had strict ‘austerity’ conditions attached to them, spelled the end of improved access to health and education, cuts in all public spending, wage freezes, spiraling unemployment and a severely reduced public sector, including health and education, which are among the biggest employers.

In 1978 Moi took over from Kenyatta, the first president after independence, and was happy to comply with the stringent conditions demanded by these international financial institutions through their structural adjustment policies, as long as it meant he could get his hands on a lot of money. He remained president for 26 years, during which time the population went from 16 million to about double that figure, while health, education, infrastructure and other sectors were held, nominally, at around 1980s levels, although these sectors declined rapidly during the Moi regime.

This is where the story becomes surprising (if you think it’s all about sex). HIV had been around for a few decades, albeit unnoticed. But it spread rapidly from some time in the 80s and prevalence probably peaked in the late 90s, at 10 or 11%. Very high death rates, peaking in the early to mid 2000s, helped ensure that prevalence was halved by 2012 or 2013, according to the latest figures (although that’s 5% of a population that is increasing at over 2.5% per annum). But why would HIV prevalence decline when the worst effects of structural adjustment policies were being felt, from early in the 1990s onward, as it appears from my (admittedly rough) chronology? The annual rate of new infections, incidence, is said to have peaked in the early 90s, which would account for a peak in prevalence a few years later, and a subsequent drop. But we associate increased levels of spending on health, education, infrastructure and the like on development, better education, and better levels of health. How could the epidemic appear to be receding at precisely this time? The country had done nothing to deserve improvement in any area of health, let alone HIV, which Moi refused to acknowledge for most of his term of office.

When I wrote the brief account of HIV in Kenya five years ago, I was still busy questioning some of the completely unexpected findings I had uncovered for my dissertation, most or all of which the HIV industry was already aware. Why were wealthier people often more likely to be infected? Why were urban dwelling people also more likely? Why were ‘unsafe’ sexual behaviors often little more associated with HIV transmission than an absence of such behaviors, or the presence of ‘safe’ sexual behaviors? In Kenya, almost all development indicators were at their lowest in the Northeastern province, but HIV prevalence was also lowest there. Condom use was minimal, fertility rates were high even for Kenya, gender inequality was high, polygamy was common, as was female genital mutilation, intergenerational sex and marriage (large differences in age between partners, usually older men and younger women) were far more common than anywhere else in the country, and many people had little knowledge of HIV.

The list continues. Population was growing rapidly in some of these areas, several were undergoing urbanization (or something similar) and population density was increasing in others. Shortly after I started studying HIV it was clear to me that it couldn’t possibly be all about heterosexual behavior, I just didn’t know what could account for very high prevalence figures in some places and low figures in others. Upon visiting Kenya in 2002, when everyone told me about ‘traditional’ practices and all manner of factors that resulted in high rates of HIV transmission, they were also talking about how ‘abstaining’ (a word I associated with religion), ‘faithfulness’ (a word I associated with courtly love) and ‘condomizing’, a word I didn’t associate with anything at all, were resulting in declining prevalence figures. How could this be, and weren’t high death rates already explaining these drops in prevalence?

Obliged to exclude certain modes of HIV transmission from my dissertation to keep it focused and within size restrictions, I was advised to lose sections on non-sexual HIV transmission. It took me a about a year to get back to that, but when I did, all the previously unexpected findings started to make sense: I was sure that HIV wasn’t solely transmitted through sex, I just didn’t know that the HIV industry had been so strenuously denying the proportion that unsafe healthcare, cosmetic and traditional practices had been contributing in the past, and were still, obviously, contributing. It became clear that the industry somehow resembled an old boy network infused with a kind of freemasonry, a fair amount of evangelical zeal, and a good helping of neo-eugenicism acquired from some of the big NGOs that got in on the HIV act early on.

HIV is transmitted through heterosexual sex, that’s not in question. But people in Northeastern province don’t have much access to healthcare, infrastructure, education or many other benefits, and that is what may have protected people living in that province from HIV. In contrast, people living close to better developed infrastructures, people in cities (especially Nairobi, Mombasa and Kisumu), wealthier people and people living closest to health facilities may have, where conditions in health facilities were not adequate, faced very high risks. They are not ‘at risk’ populations, so much as ‘populations put at risk’ by the institutions that persuade them to avail of their services but can’t always provide these services safely. There are, indeed, certain behaviors that increase the risk of being infected with HIV, but they are not all sexual behaviors, they are not all individual behaviors and they are not all the behaviors of poor, uneducated, powerless people, either.

It’s not that health, education and infrastructure are not benefits, they are. Kenyans and people of all underdeveloped countries need more healthcare, more education and more (appropriate) infrastructure, lots more than they have ever had. But unsafe healthcare can be a lot worse than no healthcare. When structural adjustment policies reduced access to the benefits of health, education and others, they may also have reduced the exposure of most people in Kenya to an important, but rarely discussed, HIV risk.

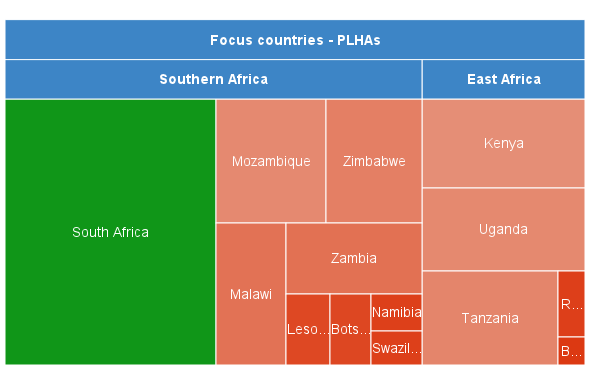

An estimated 1.6 million people are living with HIV today, but that’s a relatively small percentage of the population. HIV prevalence in countries with far better and more equitable access to health facilities, such as Botswana, is among the highest three in the world. The HIV region where the epidemic is said to have begun, with relatively poor infrastructure, also has a far less serious epidemic than the southern region. Where road networks are almost entirely absent, such as in the Northeastern province of Kenya (and some countries in low prevalence North Africa), there are few health facilities, and access to these facilities is low. But along Kenya’s best road networks (which are certainly nothing to boast about) HIV prevalence is higher. The best health facilities are not found in isolated areas, of course. But nor are the best health facilities likely to have been safe places in the 1980s and 1990s. Some of them are still unsafe, we just don’t know how unsafe, and exactly what proportion of HIV is transmitted through unsafe healthcare.

Infrastructure alone didn’t result in rapid transmission of HIV, much of that was built during the colonial period. Nor did the existence of health facilities, or even public health programs, guarantee that a HIV epidemic would be severe. But increased access to health facilities where safety standards sometimes (often?) fell below par might explain the huge increases in HIV prevalence that occurred inside very short periods. People outside of the HIV industry would wonder how a virus that is difficult to transmit through heterosexual sex could appear ti occur in ‘explosive’ outbreaks, with prevalence doubling in less than a year. The industry would assure them that ‘Africans’ clearly engage in levels of unsafe sex that is beyond what any non-Africans could manage. Those whose prejudices already matched those of the HIV institutions accepted this explanation. Anyone who continued to question such a racist view of HIV was accused of denialism and shunned by their professional colleagues (unless they didn’t have any professional colleagues, or a profession).

Much of the evidence collected over the last 30 years, even evidence collected by the HIV industry itself, points to a rule of thumb: you can not work out levels of sexual behavior from HIV prevalence; and you can not work out HIV prevalence from levels of sexual behavior. But the HIV industry, outrageously, insist that high HIV prevalence in African countries is evidence for high rates of ‘unsafe’ sexual behavior, and that high rates of sexual behavior ‘explain’ or predict high rates of transmission.

When I turned my attention to non-sexual HIV transmission I came by a small group of people who are still questioning the orthodoxy, as they had been doing for many years. Some have retired, others don’t depend on HIV related funding for their work, most are doing it for free. There are those who had been involved in HIV related work, and they are either ignored or treated with contempt for even talking about unsafe healthcare, or anything else that makes the sexual behavior paradigm look like the institutional racism that it is. The mere mention of some names involved can end a conversation, or elicit no more than a peremptory gesture, which is the only evidence the HIV industry has yet been able to muster against the possibility that non-sexual modes of transmission may make a significant contribution to the most severe HIV epidemics in Africa.

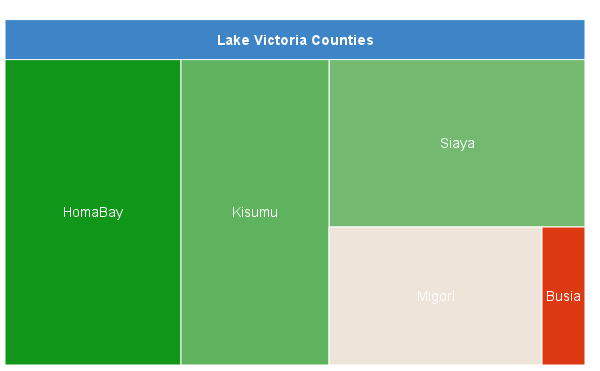

In Kenya, people will still tell you about how much ‘Africans’ love sex. If you ask why prevalence in Homa Bay, bordering on Lake Victoria, is 135 times higher than it is in Wajir, not far from the border with Somalia (though not very close to anything else worth speaking of), they will say that people around Lake Victoria love sex. Beyond that, they have no credible explanation. Every now and again there’s a flurry of activity around some issue that attracts the media’s attention and this can crop up in conversations. For example, in 2002 some people were still talking about ‘devil worship’, for which a well publicized commission was set up, and which never published the results of its inquiries. But HIV stories drowned out even stories as titillating as devil worship. People around Lake Victoria will tell you with great relish about the sexual behaviors of fishermen, ‘barmaids’, transport personnel, Ugandans, Luos (the predominant tribe around Lake Victoria) and various other groups that have at various times been held up for scrutiny by the HIV industry and, as a result, thoroughly stigmatized.

HIV has been in Kenya since just after the middle of the 20th century and it was recognized from the early 1980s. It has spread around the country, though very unevenly, perhaps over a period of 40 years. The HIV industry has convinced Kenyans that it is individual sexual behavior that ‘spreads’ HIV. But transmission rates declined before any effort was made to address the epidemic, something the HIV industry are unable to explain. So the epidemic is still very much alive, and unexplained by the orthodox story. Kenyans still don’t know what is driving the epidemic, therefore they don’t know how to prevent it from continuing.

There’s more, a lot more. Hopefully I’ll have time soon.