An estimated 1 million Kenyans are receiving antiretroviral drugs, about 64% of all HIV positive people. Partly as a result of this, death rates, along with the rate of new infections, have continued a decline that started in the early 2000s, and the early to mid 90s, respectively. Now pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) is being added to the country’s HIV strategy, a course of antiretroviral drugs taken by HIV negative people, which should significantly reduce the risk of their being infected.

So this should be a good time to look at how HIV treatment in its various forms should be targeted. ARVs are relatively straightforward, people testing positive can be put on treatment. But PrEP, if it is expected to reduce infections, needs to be prescribed for those most at risk. This is not as simple as it sounds, because HIV resources have so far been flung far and wide in Kenya, as if those who most need them will magically benefit.

The ruling assumption for high prevalence countries has been that 80-90% of all HIV transmission is a result of ‘unsafe’ sexual behavior. HIV prevalence is seen as a reliable indicator of ‘unsafe’ sexual behavior, and ‘unsafe’ sexual behavior, or perceived behavior, is seen as a reliable indicator of prevalence.

This is completely circular, of course. But if these prejudices are carried over from addressing the HIV positive population, and applied equally to the HIV negative population, the bulk of the drugs may as effectively be flushed down the toilet. The majority of Kenyans are, were, or will be sexually active. But the majority are not at risk of being infected with HIV.

Kenya’s HIV epidemic, in common with the epidemics in several other East African countries, is quite old. The virus has been circulating since the 50s and 60s, so the epidemic is about half a century old, give or take a few years. In other countries, such as the DRC, the virus has probably been around for about 100 years, although it must have affected only small numbers of people for many decades.

Don’t be fooled by figures suggesting that HIV has only been around since it was first recognized by doctors in the early 1980s (or just a little bit earlier), and later described by scientists. UNAIDS estimate that prevalence was already about 3% in Kenya by 1990, rising to over 10% later in the decade, to peak at almost 11%. From 2000, prevalence declined for a few years, rose again from 2005, then dropped to 6%.

This suggests that the rate of new infections (incidence) peaked and started to decline in the early to mid 90s, prevalence peaked and started to decline by the late 90s, and death rates would have peaked in the early 2000s. By 2007 prevalence was 8% and it is now 6%, so it has hovered between 6 and 8% for more than 10 years. Declines are slow, irrespective of major interventions.

Although the widespread use of ARVs, which began in the late 2000s, has contributed to a decline in new infections, prevalence and death rates, it is not possible to attribute these improvements to drugs alone. Making PrEP available to all those assumed to be ‘at risk’ of being infected, purely on the basis of the circular argument mentioned above means that this is going to be an expensive, but very ineffective intervention.

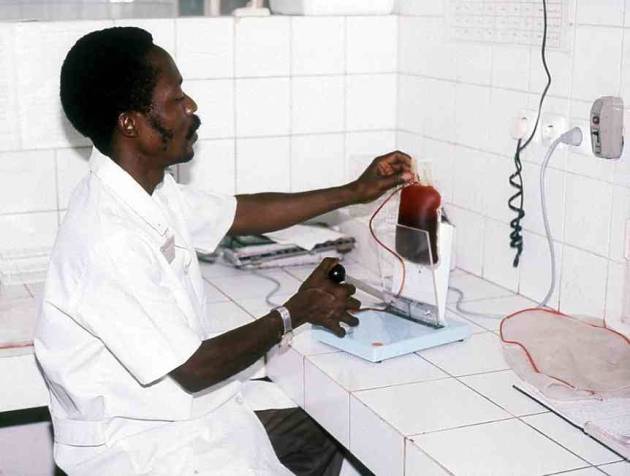

This sounds like bad news, but it doesn’t have to be seen that way. If the HIV risks people face could be identified, whether they are sexual or non-sexual, this will reduce the number of people who need PrEP. Most non-sexual risks, for example, exposure to blood and other bodily fluids through unsafe healthcare, cosmetic and traditional practices, are easily and cheaply avoided. No need to give PrEP to all the patients at a clinic when you could just clean up the clinic, right?

But also, things have changed, PrEP allows us to target those most at risk much more accurately than before. If people know they can protect themselves, they will. Clinics can now safely return to the practice of ‘contact tracing’, identifying how each person testing positive may have been infected, and then addressing that source of infection, whether it was a sexual partner, a clinic, a tattoo artist, or whatever.

The decision to discontinue tracing contacts, which was made in a very different context (a rich country, where the bulk of HIV transmissions were occurring among a relatively small population, and resulting from an easily identified set of behaviors) is inappropriate for a country with a massive HIV epidemic, where the risks have not been clearly demonstrated, and averted. In Kenya, for example, the majority of people who become infected with HIV do not face the high risks identified in rich countries, receptive anal sex and injecting drug use.

If identifying how people become infected can allow HIV negative people to avoid being infected, and allow HIV positive people to avoid infecting others, then contact tracing is vital in high prevalence countries. It is also vital if interventions such as PrEP are to be effective, or even affordable. Already, researchers have found that not being able to identify where the risks are coming from will significantly increase the quantity of drugs each person needs, in addition to vastly increasing the number of people deemed to be in need of PrEP.

Despite ample evidence that non-sexual risks are as important as sexual risks, evidence that has been available since the virus was first identified as causing Aids, most research concentrates on reporting sexual risk only, collecting data about sexual risks, recommending strategies to reduce sexual risks only, while ignoring, denying or failing to collect data on non sexual risks.

Mass ARV rollout complements pre-existing trends in HIV epidemics, though not as much as it could have, had the contribution of non-sexual transmission been acknowledged. However, PrEP will be a slow and inefficient solution unless targeted at those truly at risk, as opposed to the tens or hundreds of millions who are sexually active. People can only protect themselves if they know what the risks are, whether they do it by avoiding exposure, or by taking prophylactic drugs.