Newspapers, web, and TV have been delivering a crescendo of reports and comments on West Africa’s Ebola epidemic. A lot of what is available for public consumption scares people who are not at risk. At the same time, people at risk are not getting adequate advice from official sources to make informed decisions about how to protect themselves and their loved ones.

In this situation, it’s useful to take a look back at three well-studied and well-reported Ebola outbreaks: the first two recognized outbreaks in 1976 in Sudan and Zaire (currently Democratic Republic of the Congo) and a later outbreak in Kikwit, Zaire, in 1995. Official committees of experts studied each of these outbreaks and reported what they found in the Bulletin of the World Health Organization in 1978 and in the Journal of Infectious Diseases in 1999.

Nzara and Maridi, Sudan, 1976

The first recognized Ebola outbreak began in Southern Sudan in late June 1976 and ended in November 1976. A WHO/International Team coordinated a detailed and thorough investigation of the outbreak, reporting 284 cases and 151 deaths. Information and quotes in this and following paragraphs are from: Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1978, pp 247-270, available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/bulletin/1978/Vol56-No2/ (accessed 2 August 2014).

The outbreak in Southern Sudan was traced to infections among workers at a cotton factory in Nzara town beginning in late June. The source of the virus is suspected to be bats or other animals living in the factory. During the outbreak, 9 factory workers got ill with Ebola (p 253); most subsequent infections came from household contact. “The outbreak in Nzara died out spontaneously” (p 254) after 31 deaths. Before the Nzara outbreak ended, cases from Nzara spread Ebola to two other communities, Tembura and Maridi. In Tembura, a woman from Nzara introduced Ebola that killed three close contacts; that was the end of it in Tembura. In Maridi, Ebola spread from two people from Nzara treated at Maridi’s hospital, which “served both as the focus and the amplifier of the infection” (p 252). Transmissions in Maridi lead to 116 deaths. Several patients from Maridi went for treatment in Juba, resulting in one additional infection and death among Juba’s hospital staff.

“The difference between the Nzara and the Maridi outbreaks is best exemplified by examining the focus where patients most probably became infected. Few patients (26%) were even hospitalized in Nzara, and they seldom stayed more than a few days, but in Maridi almost three-quarters of the patients were hospitalized, and often for more than two weeks. As a result, Maridi hospital was a common source of infection (46% of cases), whereas the Nzara hospital was not (3% of cases)…” (p 253).

A WHO/International Study Team arrived in Maridi towards the end of the epidemic and stayed to the end. The Study Team recruited surveillance teams to scout for cases in communities around Maridi. “A large number of cases of active infection were soon discovered; each was reported to the Sudanese officials and an ambulance accompanied by a Public Health Officer was sent to the house. Patients were persuaded to enter the isolation wards at the hospital” (p 250). Significantly, Public Health Officers did not force suspected cases to go to the hospital: “Some refused, and in these cases relatives were warned of the grave risks, and advised to restrict close contact with the patient, and to limit it to only one close relative or friend. Protective clothing was offered but usually refused.”

Yambuku, Zaire, 1976

The first recognized case reported symptoms on 1 September. The last death occurred just over two months later on 5 November 1976. An International Commission managed a detailed and thorough investigation of the outbreak, reporting 318 cases and 280 deaths. The information in this and following paragraphs is from the Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 1978, pp 271-293, available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/bulletin/1978/Vol56-No2/ (accessed 2 August 2014).

“The index case in this outbreak had onset of symptoms on 1 September 1976, five days after receiving an injection of chloroquine for presumptive malaria at the outpatient clinic at Yambuku Mission Hospital… [A]lmost all subsequent cases had either received injections at the hospital or had had close contact with another case. Most of these occurred during the first four weeks of the epidemic, after which time the hospital was closed, 11 of the 17 staff members having died of the disease…” (p 271).

“Five syringes and needles were issued to the nursing staff [at the Yambuku Mission Hospital] each morning for use at the outpatient department [with an average of 200-400 outpatients each day], the prenatal clinic, and the inpatient wards [with 120 beds]. These syringes and needles were apparently not sterilized between their use on different patients but rinsed in a pan of warm water. At the end of the day they were sometimes boiled” (p 273).

“The epidemic reached a peak during the fourth week, at which time the YMH [Yambuku Mission Hospital] was closed [on 3 October], then it receded over the next four weeks” (p 279). “[I]t seems likely that closure of YMH [Yambuku Mission Hospital] was the single event of greatest importance in the eventual termination of the outbreak” (p 280). The last recognized transmission occurred in late October.

The International Commission organized surveillance for cases in communities around Yambuku. “Suspect cases were not closely examined, but medicines were given to them and arrangements were made for their isolation in the village… [P]hysicians were sent to follow up suspect cases…” (p 276). Notably, surveillance teams did not force or even urge suspect cases to go to hospital. In any case, the outbreak in and near Yambuku had already died out on its own, with the last probable case dying on 5 November, four days before surveillance began on 9 November (p 277).

The International Commission collected and reported data on transmission from cases to family members. In 146 families with one or more cases acquired from outside the family, 1,103 family members were exposed, of which 62 (5.6%) got sick with Ebola (p 282). In other words, there was less than a 50% chance a case would infect a family member (146 cases, or more if any family had more than one case, infected a total of 62 family members). Thus, once the hospital closed, each case infected on average less than one family member, so the epidemic died out on its own.

Kikwit, Zaire, 1999

An International Scientific Commission investigated an Ebola outbreak in Kikwit, DRC, a large, sprawling town with a population reported at 200,000-400,000 at the time of the outbreak. The investigation identified 315 cases between 6 January and 16 July; out of 310 cases with adequate information, 250 died. Information in this and subsequent paragraphs is from a 1999 special issue of the Journal of Infectious Diseases, available at: http://jid.oxfordjournals.org/content/179/Supplement_1 (accessed 3 August).

During the Kikwit outbreak, 80% of case patients were hospitalized to treat their Ebola illness (page S82). However, hospitalization did not interrupt contacts between family members and case patients (p S88): “As in much of Africa, the families of inpatients are responsible for providing food and many other aspects of patient care, such as cleaning bedpans and washing soiled clothing and linens. Often family members arrange to sleep on the hospital ward [even sharing the patient’s bed; p S90] to assure continued care through the night.”

A study of secondary infections among 173 household members of 27 case patients found 28 secondary infections in 15 households (7 had >1 secondary case). “The exposure that was most strongly predictive of risk for secondary transmission was direct physical contact with the ill family member, either at home in the early phase of illness or during the hospitalization” (p S89). The 28 secondary cases occurred in 95 household members who had touched the case patient during early or late illness; whereas none of 78 household members who had not touched the patient at that time got sick, even though many slept in the same room, shared meals, or touched the patient before illness (p S89).

“There was an additional risk associated with a variety of exposures to patients in the terminal stages of illness, such as sharing a hospital bed or hospital meals and touching the cadaver” (p S90). “[T]he use of barrier precautions by household members and standard universal precautions in hospitals would have prevented the majority of infections and deaths…” (p S91).

During case surveillance in and around Kikwit town (p S78), “persons who met the case definition…were instructed to seek medical evaluation and possible hospitalization at Kikwit General Hospital…” However, this was not forced; if the sick person chose to stay home, family members “were educated on how to reduce their risk of infection…. Nurses previously trained in the sentinel clinics also visited household of probable case-patients to distribute protective materials (eg, a pair of gloves, soap, and wash basin) as needed and to reinforce educational messages about risks of transmission and symptoms suggesting disease in subsequent family members.” During surveillance outside Kikwit (p S78-S79), “Probable case-patients were confined in their households, instructions for care were given, and basic protective equipment was provided to the primary care givers.”

Lessons for West Africa, 2014

Based on reports from previous epidemics, here are several recommendations. The first is for people at risk to protect themselves. The second is for public health managers to deal with cases in a way that is acceptable to the community while at the same time ensuring transmission is too low to sustain the outbreak. Stopping the outbreak involves reducing the average transmission from each current case to less than one more case. Both recommendations contribute to that goal.

1. Recommendation to the public: If you are living in a community with Ebola cases, avoid injections, infusions, dental care, manicures, and all other skin-piercing procedures with instruments that might not have been sterilized after previous use. If you do this, and if you stay away from people with suspected Ebola infections, you have virtually no risk to get Ebola.

If someone stays away from sick people and funerals, the only remaining risk to get Ebola is through unrecognized contact with some unknown case. In previous epidemics, acquisition of Ebola from unrecognized contacts with unknown strangers has been confirmed through only one form of contact – blood-to-blood contact when health care workers reuse syringes and needles without sterilization to give injections to one patient after another. Reused, unsterilized skin-piercing equipment can pass Ebola from someone with the virus to complete strangers. If people in communities with Ebola avoid skin-piercing procedures – in hospitals, pharmacies, dental clinics, barbershops, beauty salons, from traditional healers, etc – the risk to get Ebola from some unknown source is near zero. Moreover, the public health risk – that people with Ebola will infect strangers not involved in patient care – will be too low to sustain the outbreak. (If you do go for an injection, manicure, or other skin-piercing procedure, you can ensure instruments used on you are sterile by following advice at: http://dontgetstuck.org/.)

2. Recommendation to public health managers: Accept and accommodate home-based care of suspected and even confirmed cases, if that is what the family wants.

For the sake of effective management of the epidemic, the challenge is to reduce transmission on average from each case to less than one more case. Based on reports from three well-studied outbreaks in 1976 and 1995, caring for an Ebola case at home results on average in less than one new case – that is enough to wind down the epidemic, which is a lot better than what has been achieved so far in West Africa in recent months.

If a suspected case with common symptoms (fever, diarrhea, sore throat) goes to the Ebola ward, what is the chance he or she does not have Ebola? If so, what is the chance he or she will get Ebola from another patient? Without good data showing near zero risk for patients to get Ebola in an Ebola ward, it is reasonable for people to fear and resist going there. And, because getting all cases into isolation wards is not necessary to stop the epidemic (see previous paragraph), there is no good public health excuse for using government coercion to force people to go. Can we expect parents willingly to send children with sore throats to isolation wards?

The risk to family care-givers is, nevertheless, substantial if the suspected case turns out to have Ebola. If families accept the risk, that’s their choice. However, that risk can be reduced by giving care-givers detailed advice about specific risks, providing protective gear, and advising in-house quarantine measures to protect family members and others.

In any case, forcing suspected cases to go to isolation wards is likely to undermine rather than enhance epidemic control. Consider: When people are afraid government will force them or their loved ones to go to an Ebola ward, they may hide sick family members (suspected cases), avoid public health personnel, and seek secret treatment from cooperative doctors or others who may or may not practice barrier nursing or sterilize instruments after use. Thus, the threat of force may well reduce, not enhance, the ability of public health managers to advise and to supervise treatment of cases to prevent onward transmission.

This recommendation to accommodate home-based care agrees with a recent decision by Sierra Leone’s President Ernest Bai Koroma to quarantine sick patients at home, a decision appreciated by Heinz Feldman at the US National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: “It could be helpful for the government to have powers to isolate and quarantine people and it’s certainly better than what’s been done so far…” See: West African outbreak tops 700 deaths, Associated Press 31 July 2014, available at: http://www.patriotledger.com/article/ZZ/20140731/NEWS/140739987/12662/NEWS (accessed 31 July 2014).

Risks the current outbreak will spread to other countries

Are people living in the US or UK or Australia at risk? No. Just as in Maridi, Sudan, in 1976, the risk is that a patient with Ebola acquired elsewhere will go to a hospital with poor infection control, and that the hospital will amplify the infection, spreading it into the community. This is not going to happen in Europe, the US, or most other countries because hospitals with adequate infection control will not amplify the outbreak.

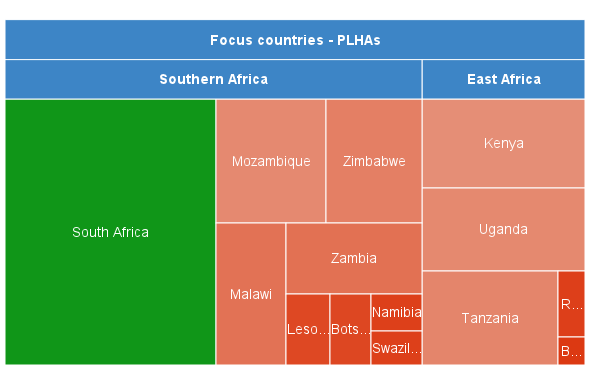

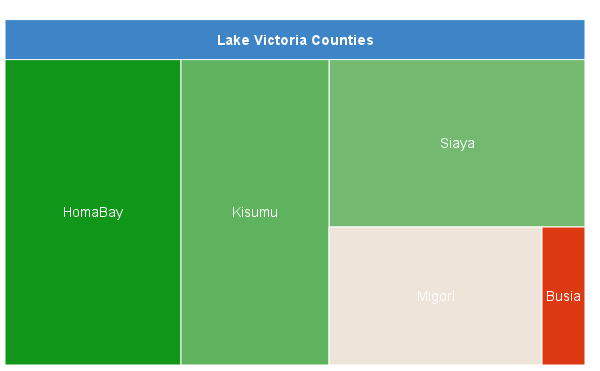

However, there is a risk that Ebola from West Africa’s ongoing outbreak might spread to other countries in Africa. Wherever HIV, a slow-acting bloodborne virus, transmits through unsafe healthcare, there is a risk that Ebola, with an incubation period of weeks not years, will similarly spread through unsafe healthcare. Most countries in Africa have generalized HIV epidemics, with more women than men infected, and with only small minorities of infections explained by men having sex with men or people injecting illegal drugs. The public health community likes to blame Africa’s generalized epidemics on sex, but no one has been able to find sexual differences between Africa vs. Europe or the US that could explain Africa’s generalized HIV epidemics. What is different is that Africans get more exposures to reused but unsterilized skin-piercing instruments during health care and cosmetic services.

The existence of generalized HIV epidemics in a country is best explained by a lot of HIV transmission through unsafe health care along with some sexual transmission. The fear that Ebola from West Africa might spread to other countries is a realistic concern for countries with generalized HIV epidemics.